AI

LLM

LatentMAS: The Secret of AI Agents That Think Without Words, Boost Accuracy, and Save Up to 80% on Tokens

If you strip away the marketing hype surrounding "agent systems," the reality is quite prosaic: as soon as you assemble a chain of several LLM agents, your token bill and latency skyrocket. Judging by experiments in LatentMAS, a classic textual multi-agent pipeline for Olympiad-level problems (AIME-24/25) easily burns through tens of thousands of output tokens for a single problem, often exceeding 20k tokens for one solution. And this isn't an abstract academic problem: anyone who has tried to piece together a ReAct/AutoGen/CAMEL-like pipeline for production quickly encountered the same pitfalls — growing context, slow responses, and the feeling that the model is less engaged in reasoning than in merely transferring text from prompt to prompt.

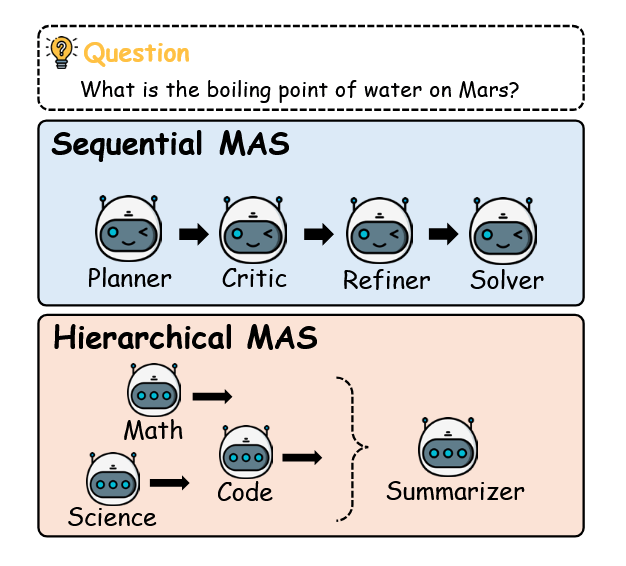

If we elaborate on this picture, the typical scenario looks quite monotonous. We have a sequential MAS: planner, critic, refiner, solver. This exact chain-of-agents is used by the LatentMAS authors as a textual baseline in their experiments. The planner outlines a solution plan in CoT style, the critic adds its "review" on top, the refiner rewrites everything once more, and the solver tries to assemble the final answer from this scattering of tokens. Each step is a new piece of text carefully appended to the next agent's prompt. As a result, the dialogue length grows like a snowball, and the token counter looks like an LLM request log that was forgotten to be stopped overnight.

The problem is that such an architecture strikes on three fronts simultaneously. First, the linearly growing textual context results in a quadratic attention cost with sequence length (on the order of O(n^2) for standard self-attention): the more agents have "talked," the more expensive each subsequent reasoning step becomes. Second, each agent is forced to re-encode all previous discussion back into latent space, reprocessing what the previous agent had already computed through its layers. Third, textual CoT chains are prone to verbosity: for complex mathematical problems like AIME and GPQA, textual MAS generates from several thousand to tens of thousands of tokens, whereas LatentMAS achieves comparable or better accuracy using fewer than fifty "latent reasoning steps" in the latent space. Even if textual agents are accelerated via vLLM, LatentMAS remains 2.6–7 times faster in end-to-end time in experiments.

Intuitively, this is similar to a team of engineers discussing a complex project only through long voice messages and emails, ignoring the fact that they have a shared repository and shared docs. Every time you need to bring another person in, you forward them the entire chat history and wait for them to digest it, instead of giving them access to already assembled artifacts – diagrams, schematics, intermediate calculations. LatentMAS proceeds from the opposite idea: if the model already stores the full history of internal states in its KV cache, why not use it as an interface between agents, rather than endlessly cycling the same text through them?

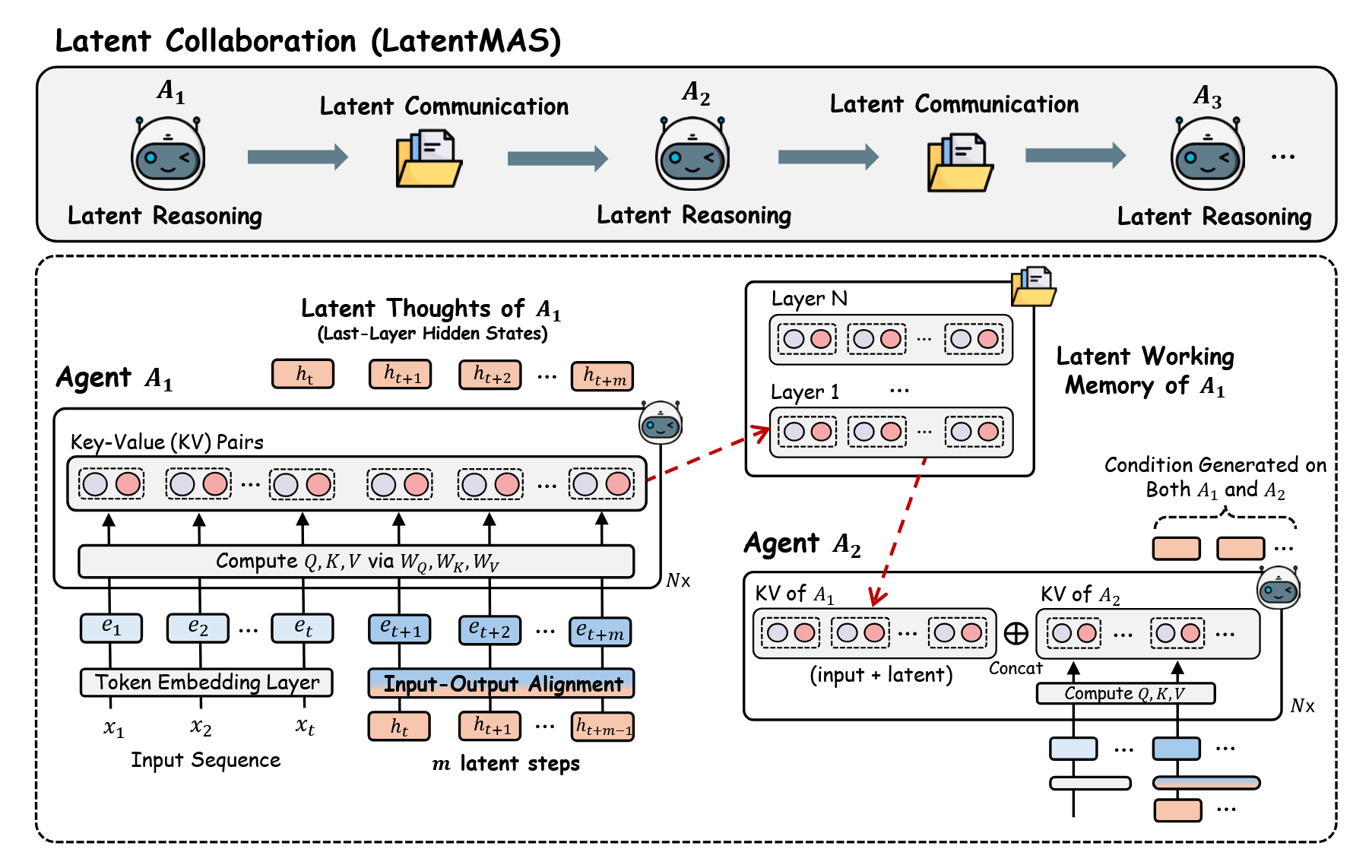

Hence a radical move: in LatentMAS, agents stop communicating with each other using text. Each agent generates auto-regression not in the token space, but in the space of the last hidden states — so-called latent thoughts — and then puts the entire accumulated KV cache into a shared "latent working memory," accessible to the next agent. Only the very last participant in the chain decodes the final answer into natural language. Across nine benchmarks — from GSM8K and AIME-24/25 to GPQA-Diamond, MedQA, ARC, and HumanEval-Plus — such purely latent collaboration yields a double-digit accuracy increase, radical token savings, and inference acceleration by several times compared to textual MAS with the same base Qwen3-4B/8B/14B models, and without any additional training. This is no longer about "slightly optimizing CoT," but about a different mode of existence for an agent system, where text becomes only a thin interface at the output, not the primary carrier of thought.

I find it easiest to think of it this way: classic TextMAS is an agent chat, while LatentMAS is a shared "memory workspace" where each agent deposits their thoughts as vectors, not paragraphs. In the first case, you endlessly retell the essence of the project to each other in words; in the second, you simply open the same multi-layered working file and continue editing it where your colleague left off. The authors formalize this idea as shared latent working memory on top of the KV cache and then show that with this scheme, no information is lost compared to textual exchanges, and the computational complexity for the same "semantic power" is lower. And here, the inevitable next question arises, which will permeate the rest of the article: if agents no longer need text to understand each other, what does their memory look like internally, and what exactly are these latent thoughts?

Basic Intuition: What are KV Cache and Latent Thoughts

To understand how agents can "talk with thoughts," one needs to descend below the level of textual tokens and see what happens inside a decoder-only Transformer during generation. The model already has built-in operational memory that stores the entire history of internal computations—this is the KV cache. Usually, it's only remembered as an engineering trick for acceleration: the model doesn't recompute all attention from scratch at each step, but saves keys and values from previous tokens and reuses them. But looking broader, the KV cache is a dynamic working memory where new fragments of the model's internal representations are appended at each step, layer by layer and token by token. In fact, it stores what the model has already "seen" and "processed" during generation.

At each generation step, the model takes the embedding of a new token, computes the next keys and values for it, and simply appends them to the existing cache. This accumulative nature makes the KV cache a natural candidate for carrying collective memory: it already contains the entire history of input and reasoning for the current agent. The authors of LatentMAS use this observation as a starting point: if all the information needed for attention already resides in the KV cache, there is no need to force agents to reiterate the same thoughts to each other in textual form. It is much more logical to learn how to transfer the cache itself from one agent to another, so that the next agent immediately gains access to the internal "thought process" of the previous one, without repeated text encoding and decoding.

Having abandoned text exchange, the next question must be answered: how can the model continue to "think" internally if the intermediate reasoning steps do not culminate in tokens? In LatentMAS, this is resolved through the mechanism of auto-regressive latent thoughts. Instead of the classic scheme where the hidden state of the last layer is transformed into a distribution over the vocabulary and generates the next token, the model uses these same hidden states as building blocks for further thinking. Each new state is brought into a format compatible with input embeddings and fed back as the next "thought step." This creates a sequence not of discrete tokens, but of continuous, dense vectors, which the authors call latent thoughts.

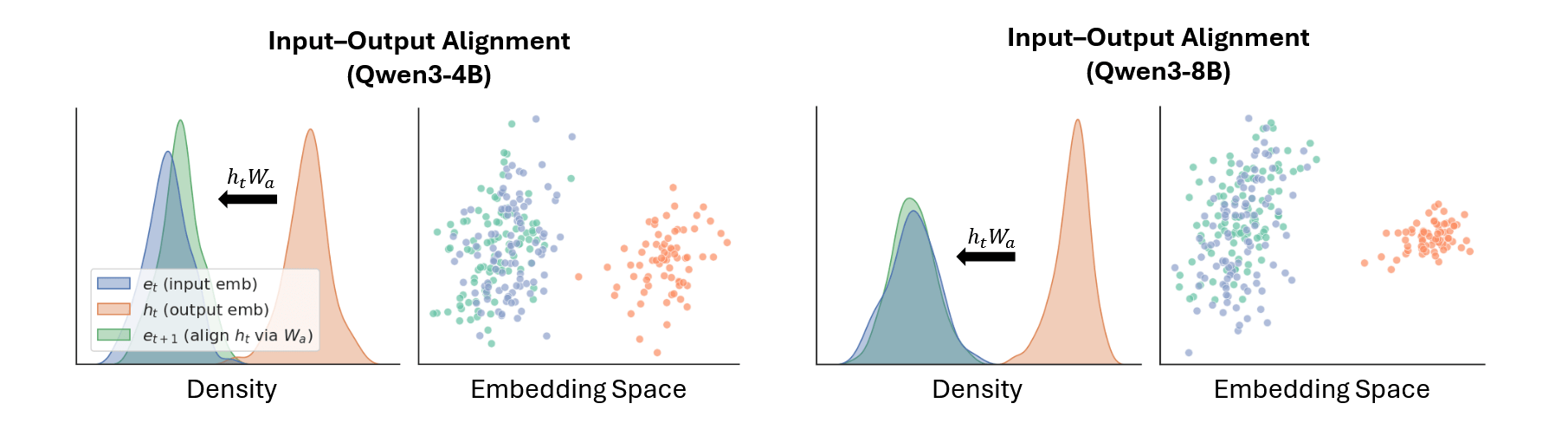

Here arises an important technical subtlety — input-output alignment. The hidden states of the top layer differ in distribution and geometry from ordinary input embeddings: if one simply feeds them back as input, the model will quickly move outside the space in which it was trained. This leads to activation drift and quality degradation. To avoid this, the authors construct a linear alignment operator that translates the output vectors into an area where they "look" like valid input embeddings. Practically, this is implemented as a small matrix calculated in advance based on the input and output embedding layers. It is calculated once and then reused for all latent steps, so overhead is minimal, and model stability significantly increases.

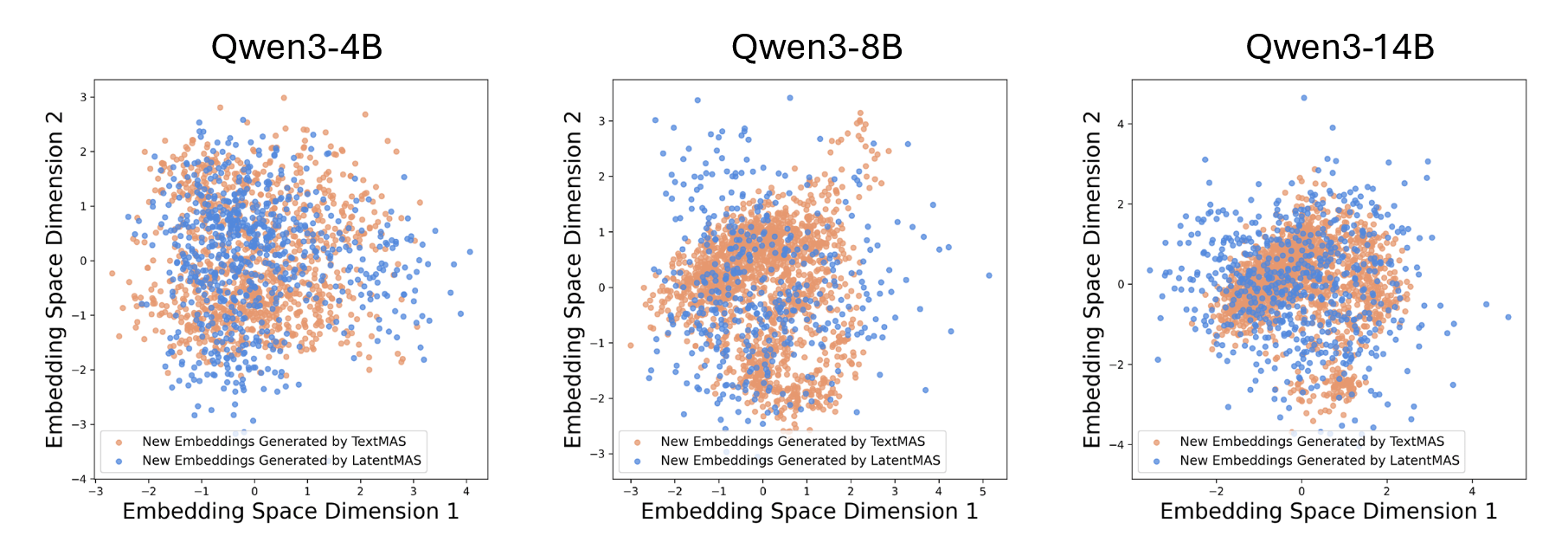

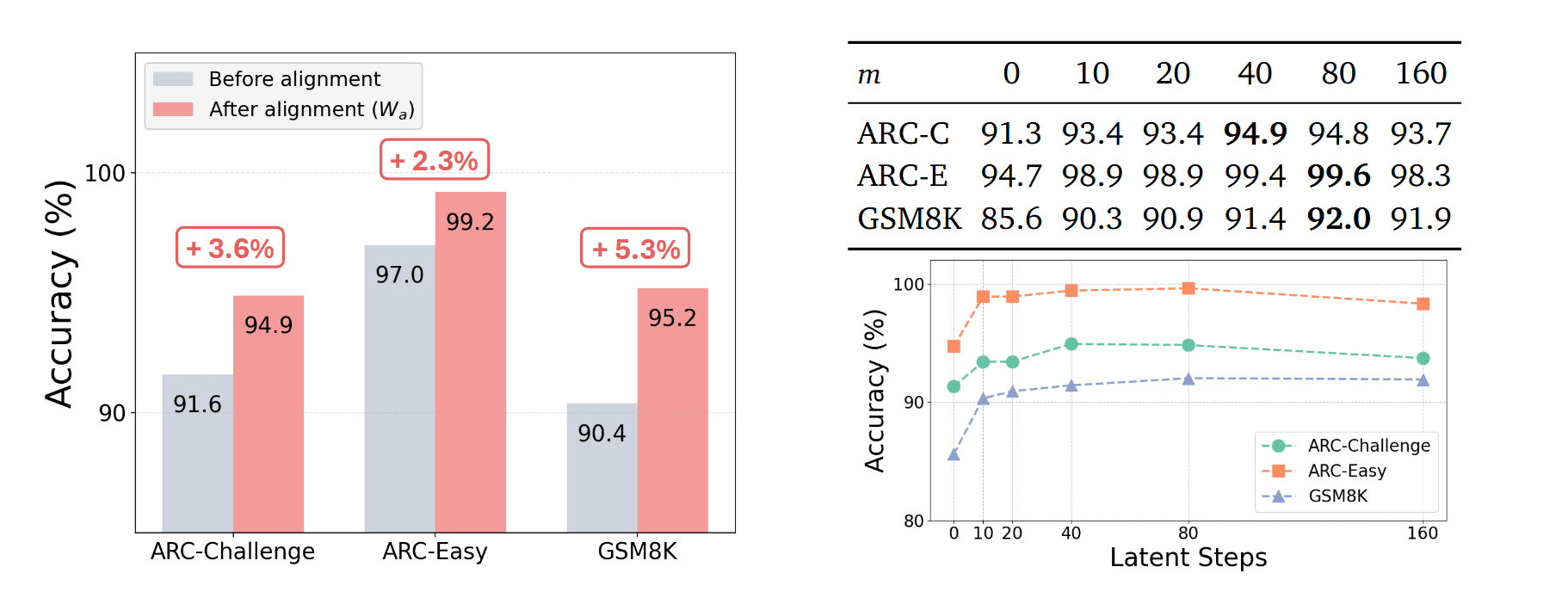

Experiments confirm that this is not a cosmetic detail, but a critical element. Visual analysis of distributions shows that without alignment, the new output vectors noticeably drift away from the region where normal input embeddings reside, whereas after applying the alignment operator, their geometry and density again coincide with the original space. At the metric level, this yields an additional 2.3–5.3 percentage points of accuracy on various benchmarks when alignment is enabled. Separately, the authors investigate how many latent steps are even meaningful: quality consistently increases up to approximately 40–80 steps, after which it either plateaus or slightly decreases, which aligns well with the idea of "several dozen meaningful thought steps" instead of tens of thousands of tokens in classic CoT.

Fig. 6. How the number of latent steps affects quality: on ARC-Challenge, ARC-Easy, and GSM8K tasks, accuracy increases with the depth of latent reasoning and stabilizes in the range of approximately 40–80 steps, after which it begins to plateau or slightly decrease.

Intuitively, all this can be understood through an analogy. Textual reasoning is like vocalizing your thoughts, one word at a time from a limited vocabulary. Latent thoughts are your internal vector language, where each step is a rich, multidimensional vector capable of carrying much more semantics than a single token. The linear alignment operator in this picture is a "translator" between the voice of internal thought and the model's internal "keyboard," ensuring that it continues to think in the correct format. Theoretical analysis in LatentMAS formalizes this intuition: under certain assumptions, one step of latent reasoning can be approximately log |V| times more effective than textual reasoning, which for the Qwen3 models used in the paper, leads to gains of the order of hundreds of times in potential expressiveness per step. And once it turns out that an individual agent can reason this way and stores the entire history of these reasonings in its KV cache, the natural next question is: how to turn this individual memory into a shared workspace for the entire agent system? This is precisely what LatentMAS answers with the concept of shared latent working memory, which we will now turn to.

Latent Working Memory: How Agents Truly Exchange Thoughts

By this point, the picture inside a single agent is clear enough: it can continue to reason in latent space, generating a sequence of hidden states instead of a stream of tokens, and the KV cache acts as operational memory for these thoughts. The next logical step is to transform this individual KV memory into a collective workspace where agents leave each other not textual summaries, but raw vector traces of their reasoning. This is precisely what LatentMAS formalizes under the name latent working memory.

The authors carefully define what constitutes agent A₁'s "working memory." Imagine that it has read the initial context (question plus instructions for its role) and taken several dozen latent thought steps. At each layer, it has accumulated key and value matrices in the KV cache: rows represent different time steps, columns represent components of the hidden state. The Latent working memory of this agent is simply a collection of all these pairs of matrices across layers. In human terms, it's a complete snapshot of what the agent has seen and thought about: from the initial question tokens to all generated latent thoughts, neatly organized by model layers.

Now agent A₂ comes into play. In a classic textual MAS, it would receive a long CoT response from A₁ as input, re-run this text through its embeddings and layers, reassemble the KV cache, and only then begin its own reasoning. In LatentMAS, this second pass is not required: instead of text, A₂ receives a ready-made KV cache from A₁'s latent working memory. Before starting its latent thoughts, it takes its current cache and simply adds blocks from the first agent's memory to it. At each layer, the temporal axis expands: its attention can look at both its own local context and the full history of A₁'s internal states. This is like not retelling your colleague your train of thought in words, but simply sending them the entire working notebook with diagrams and notes, and they continue to add new pages directly to it.

Importantly, LatentMAS transfers the KV cache, not raw hidden states of the last layer. This yields two practical advantages. First, there's no need to re-pass the incoming vectors through self-attention—they are already in the form that the attention mechanism expects. Second, the KV cache simultaneously encodes both the original textual context and the entire sequence of latent thoughts, not just the "starting prefix" of the input. Unlike simple prefix sharing, where different models share a cache only for initial tokens, here it's about the full history of reasoning of the previous agent, accessible to the next without re-encoding.

A natural question arises: is anything important lost during such an exchange compared to the classic scheme of "generated text – handed text to the next agent"? The theoretical result answers this, formulated in the paper as Theorem 3.3 (Information Preservation via Latent Working Memory). Essentially, this theorem states that with ideal transfer of latent working memory, the next agent can arrive at the same outputs as in a textual MAS, where it is explicitly given the predecessors' responses as input and re-encodes them itself. Intuitively, this looks like: text is a quantized, compressed projection of hidden states into the vocabulary space, while the KV cache contains these states before the compression stage into tokens. If you were to generate text and give it to the second agent, it would pass it through its embeddings and layers and eventually end up in roughly the same region of the hidden space that LatentMAS transmits directly through the cache.

A visual analogy works very well here: transmitting thoughts via text is like sharing a JPEG instead of the original multi-layered PSD file. In textual MAS, you give the next agent an already flattened picture of reasoning – the final render of CoT, where most intermediate layers and details are lost. In LatentMAS, you send the "PSD" itself: all attention layers, all intermediate activations, all thought drafts are in the KV cache. The second agent can draw its layers on top of them, without starting from a blank canvas and without trying to reconstruct missing details from a compressed JPEG.

The formal bonus of this scheme lies not only in information preservation but also in computational cost. Earlier in the paper, a theorem is introduced showing that for the same semantic power of a textual sequence, it requires several times more steps due to vocabulary limitations: one step of latent reasoning can carry semantics comparable to hundreds of tokens. Based on this, the authors analyze the complexity of LatentMAS and conclude that for a fixed "depth" of reasoning, its computational cost is significantly lower than that of textual MAS with the same level of expressiveness. This is especially noticeable in scenarios like AIME or GPQA, where textual CoT can occupy tens of thousands of tokens, while LatentMAS achieves comparable or better accuracy in several tens of latent steps.

If we return to the intuitive picture of a multi-agent system, the difference between TextMAS and LatentMAS becomes almost caricatural. In the first case, agents queue up at the microphone and take turns delivering long speeches. Each subsequent agent must first listen to everything preceding it, and then translate it back into its own internal schemas. In the second case, they have a shared "memory notebook" on the table — that very layered KV cache — and each simply adds their schemas and formulas there, seeing the full context. Theoretical results in LatentMAS state: in terms of content, these two processes can be equivalent, but working with a shared notebook is significantly cheaper than endless verbal retellings. The next act will show precisely how this seemingly purely architectural idea translates into very tangible gains in accuracy, tokens, and latency on real benchmarks.

Experimental View: Numbers That Change Architecture

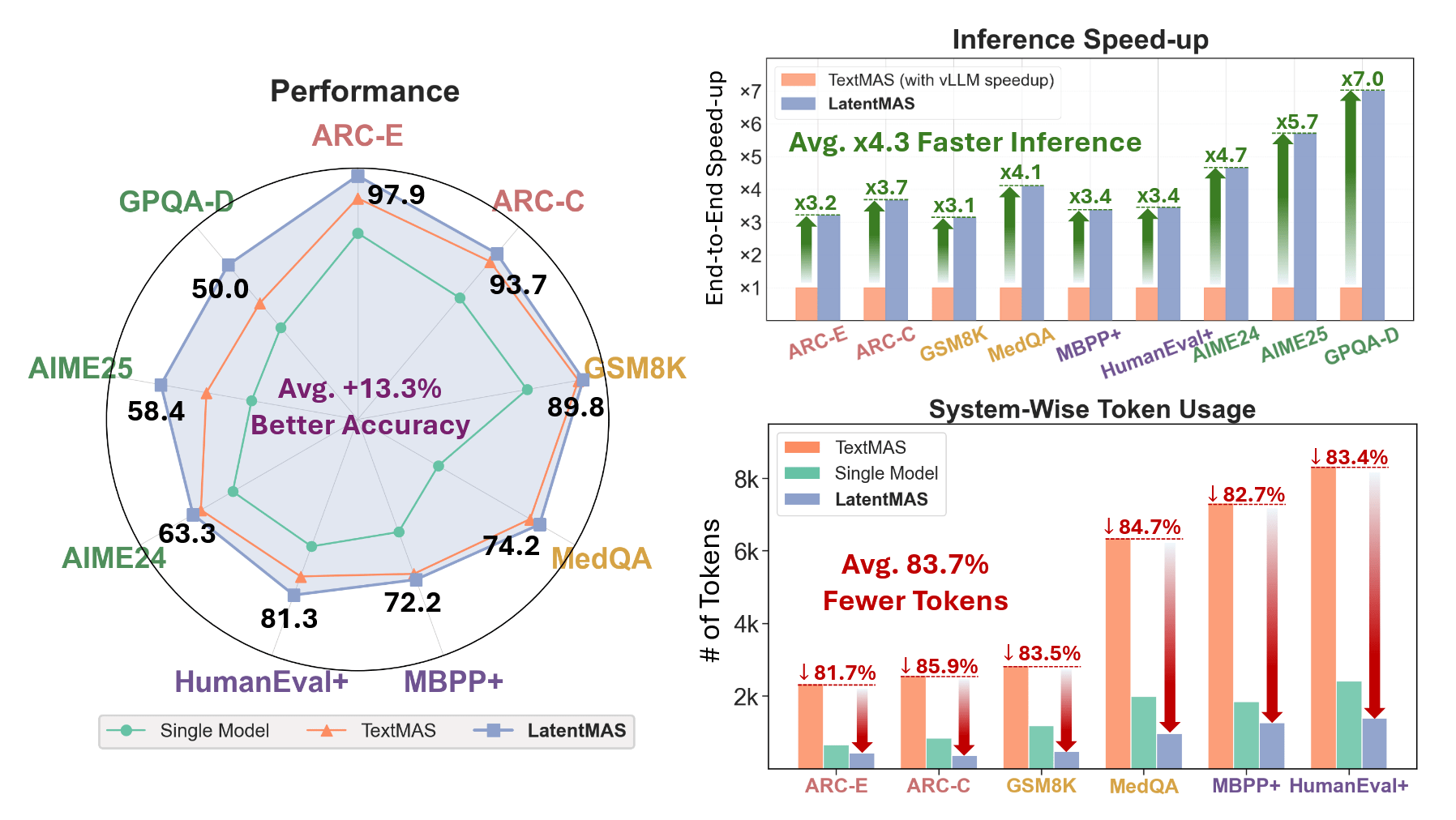

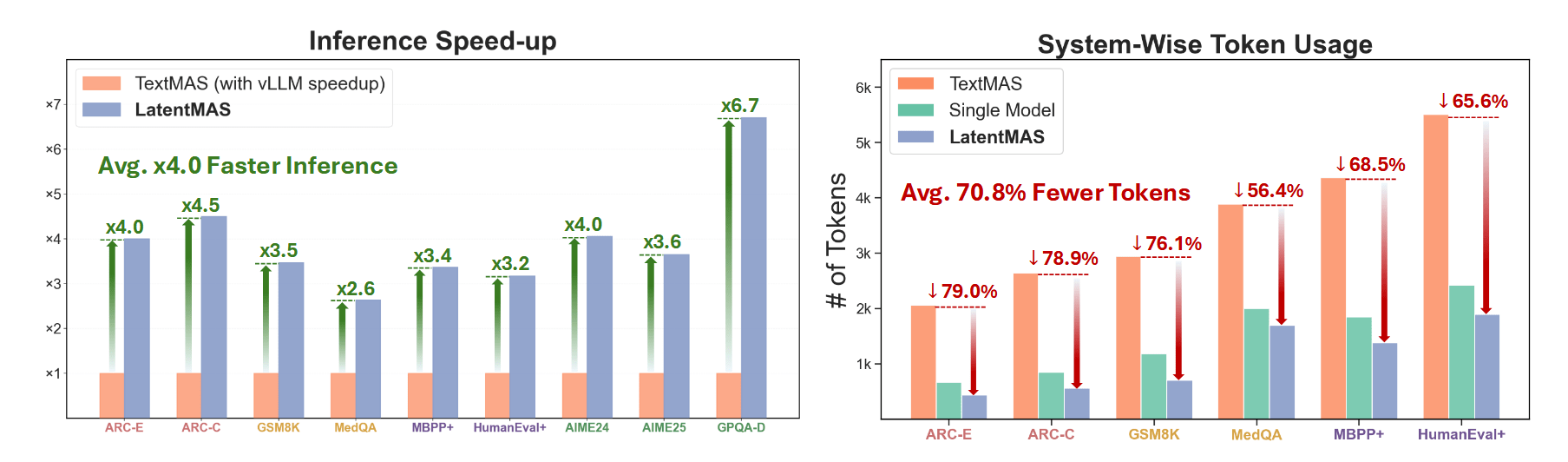

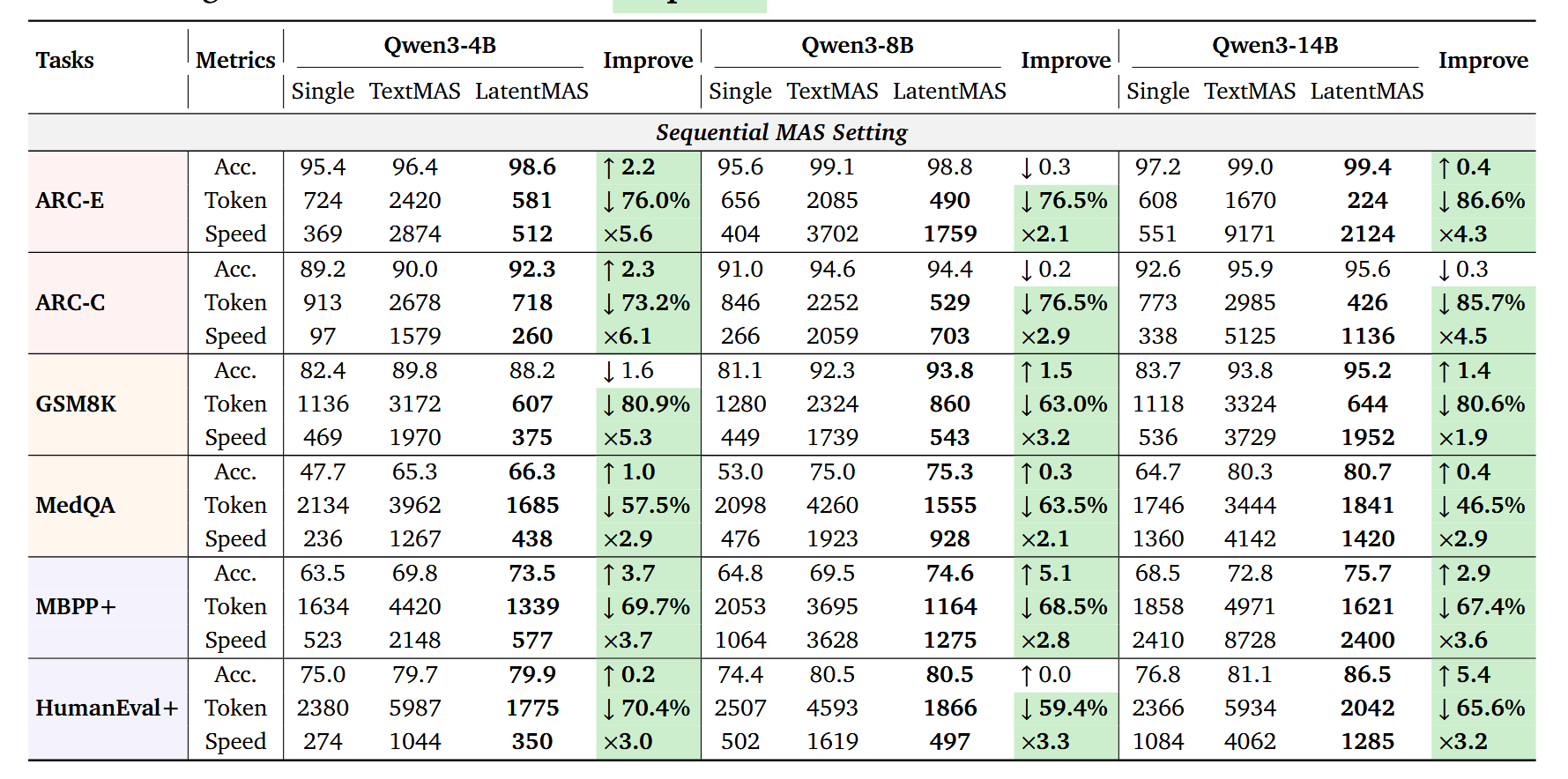

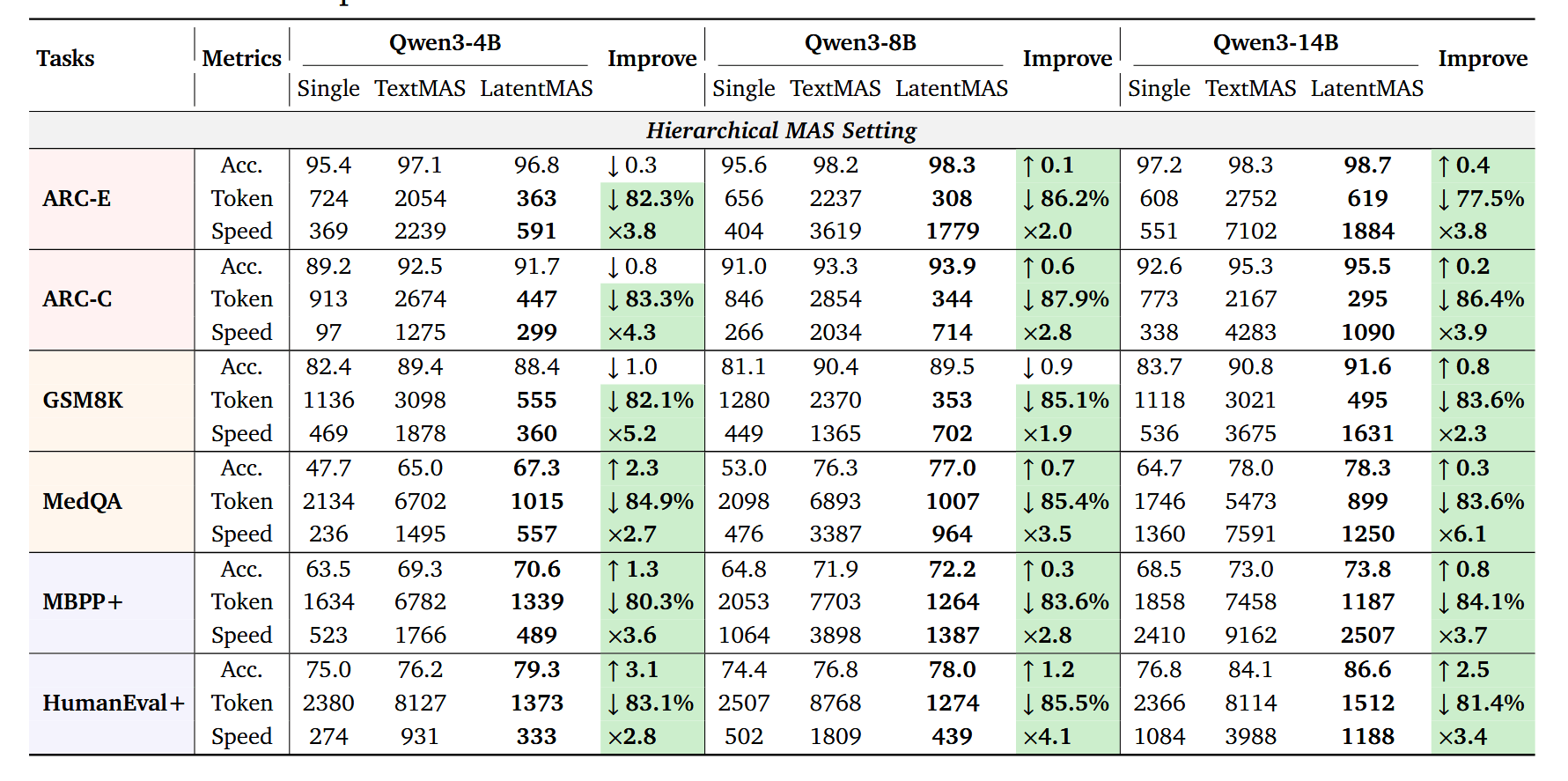

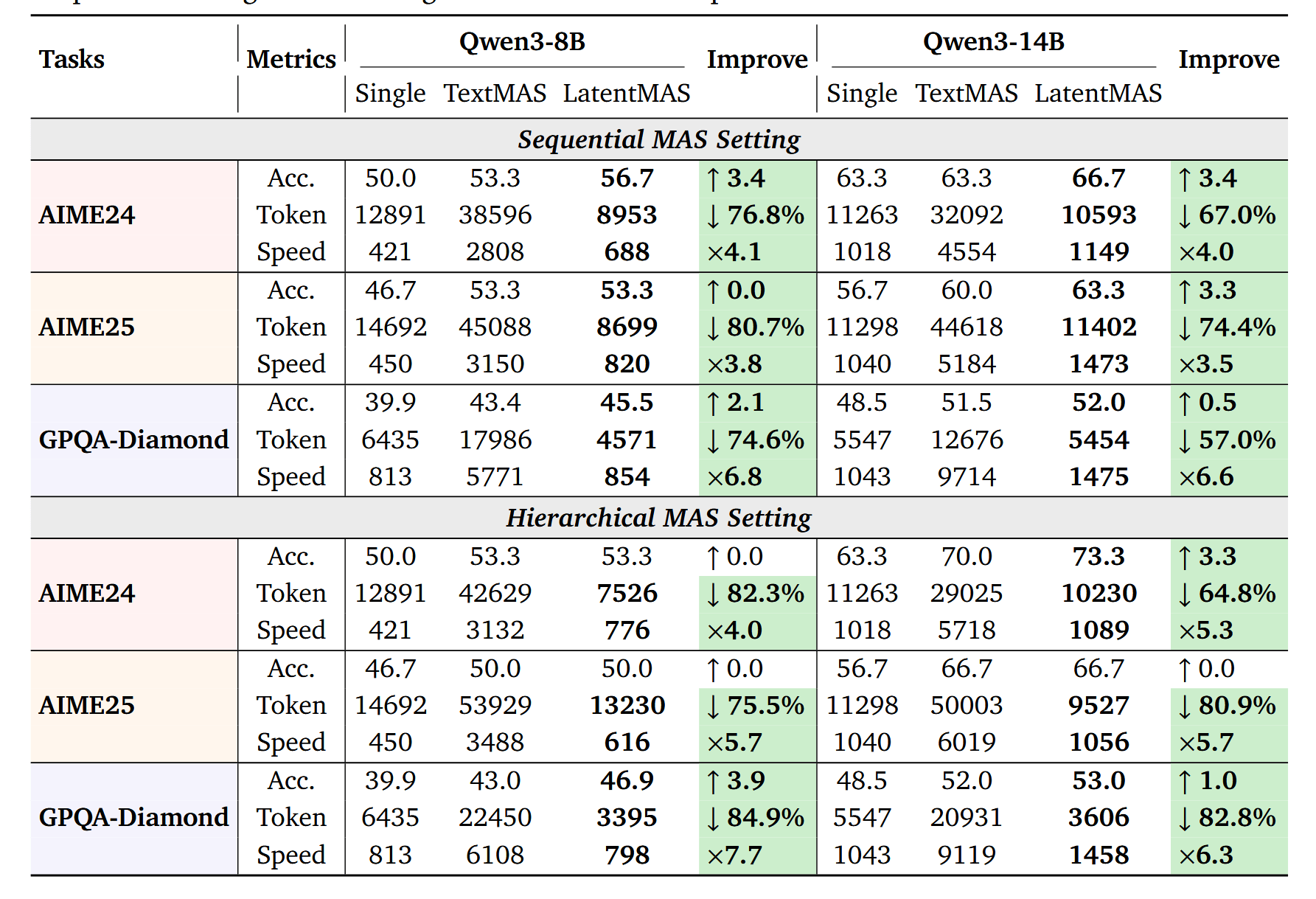

After three acts on the structure of latent memory, it's easy to dismiss everything as beautiful theory: "well, yes, latent thoughts, KV cache, theorems… but does it work in production?" The authors of LatentMAS answer this very aggressively, not with abstract pictures, but with a dense table of nine benchmarks, three model sizes, and two types of MAS architectures. Simply by replacing textual agent communication with latent working memory, the system achieves an increase of up to 14.6 p.p. in accuracy, a 70.8–83.7% reduction in the number of output tokens, and an average 4–4.3x inference speedup compared to textual MAS, all without additional training and on the same Qwen3-4B/8B/14B models.

The experimental structure is quite fair. On one side—a strong single-model baseline that simply generates an answer token by token without any agents. On the other—two variants of textual MAS: sequential (planner → critic → refiner → solver) and hierarchical (math/code/science agents + summarizer), both built on the same models and prompts as LatentMAS, but communicating via text. On the third—LatentMAS in the same two configurations, where the only fundamental difference is that CoT dialogues between agents are replaced by latent thoughts plus KV cache transfer. All three camps are run on the same set of nine datasets: GSM8K, AIME-24/25, GPQA-Diamond, MedQA, ARC-Easy/Challenge, MBPP-Plus, and HumanEval-Plus.

When looking at "general" tasks—school mathematics, commonsense, and code—the picture is quite systemic. On GSM8K, ARC-Easy/Challenge, MedQA, MBPP, and HumanEval, LatentMAS almost always surpasses the single-model in accuracy (an average of about 14 percentage points gain in sequential setup) and further adds a few points compared to textual MAS. At the same time, the token disparity looks particularly indecent: the sequential variant of LatentMAS spends approximately 3–5 times fewer tokens on answers than TextMAS, while the hierarchical version sometimes achieves up to 80% savings, which is clearly visible in the summary tables and Fig. 8. For latency, it's much the same: an average 4x speedup relative to textual MAS plus a bonus against the single-model due to the final agent in LatentMAS decoding on a very short tail.

But the real test of the concept is, of course, the "hard" reasoning benchmarks: AIME-24/25 and GPQA-Diamond. It is there that classic CoT chains particularly love to balloon to indecent sizes—the table shows that textual MAS easily exceeds 20k output tokens for a single AIME problem and tens of thousands of tokens for GPQA. Against this backdrop, LatentMAS looks like a system from another world: in sequential mode for Qwen3-8B and 14B, it achieves the same or better accuracy on AIME-24/25 and GPQA-Diamond, using significantly fewer tokens (around 9–11 thousand instead of 30–45 thousand) and only a few dozen latent steps, not thousands of CoT tokens. In terms of inference time, the gap is even more striking: even if both camps are given vLLM as an accelerator, LatentMAS remains 2.6–7x faster than textual MAS on the same tasks, simply because it hardly decodes any text within the system.

It is clearly visible how the theoretical log |V|-advantage of latent steps materializes into engineering numbers. Where TextMAS is forced to step through a discrete vocabulary, generating a long sequence of tokens, LatentMAS performs a few dozen dense vector steps and then a short text output. Fig. 9 visually emphasizes this: on the left are time bars, where LatentMAS is consistently faster than both single-model and TextMAS (even when using vLLM), on the right are token bars, where the latent approach saves from 60 to almost 90% compared to textual agent interaction. An interesting side effect emerges: a system with latent memory often uses fewer tokens than a single model, because the final agent decodes a very short output, relying on the rich KV memory of previous agents.

It is worth dwelling separately on the analysis of the latent space, because it addresses an important skepticism: "what if all these latent thoughts are just pretty noise?" On MedQA, the authors take 300 questions and compare the distributions of token embeddings generated by TextMAS during CoT with the embeddings of LatentMAS latent thoughts. It turns out that latent vectors fill practically the same area of space as textual responses, but at the same time, they cover it more broadly, demonstrating greater diversity and expressiveness. After applying the alignment matrix, the new embeddings return to the "correct" input subspace, which is clearly visible in the visualizations, and on downstream metrics, this yields those same +2.3–5.3 p.p. accuracy. In the analysis of the number of latent steps, it is also visible how increasing their number to the range of 40–80 consistently improves quality, after which the curve flattens out — additional steps add almost no benefit and may even introduce slight noise.

This entire experimental section combined produces a rather strong effect: LatentMAS appears not as "just another trick on top of CoT," but as a full-fledged alternative to textual MAS pipelines with a convincing accuracy / tokens / latency profile. This is very similar to a team transitioning from endless email correspondence to working in a shared Notion: fewer emails, more work. And here, the question for practitioners becomes especially pertinent: are you willing to continue paying for tens of thousands of reasoning tokens if the same agents can agree in a few dozen latent steps, relying on shared working memory?

Practical Value and Risks: An Engineer's Perspective

After all the theorems and beautiful pictures, the most interesting part begins where LatentMAS clashes with your existing pipelines. If you currently have a sequential MAS in the style of planner/critic/refiner/solver running, LatentMAS offers a fairly straightforward path to "reflashing" it into latent mode: you keep the same role logic, the same prompts, and the same Qwen3-4B/8B/14B model, but instead of long CoT responses between agents, you organize the transfer of latent working memory via the KV cache and ask only the final agent to decode text. In the paper, precisely such a four-agent chain is used as the basic architecture for both textual MAS and LatentMAS, and merely replacing textual communication with latent communication yields those same gains in accuracy, tokens, and latency discussed above. Essentially, this is the first design prompt: take your current sequential MAS and ask not "what other agents should I add?", but "where can I remove text from the equation and leave only memory exchange?"

The second natural pattern is a latent version of hierarchical MAS. In the original work, this involves domain experts (math, code, science) plus a summarizer that receives their answers and compiles the result. In the textual version, each expert returns their long textual analysis, the summarizer is forced to read this entire CoT stream, and this is why both tokens and time are so easily inflated. In LatentMAS, experts output not tokens, but sequences of latent thoughts; their KV caches layer by layer go into the shared latent working memory, and the summarizer directly views this "multi-layered PSD" instead of a bunch of JPEG summaries, decoding only the final answer. The practical option for an engineer looks like this: keep the summarizer textual (for interpretability), but shift everything that happens before it — domain reasoning, checks, internal debates between experts — as much as possible into the latent space. In experiments, this LatentMAS configuration outperforms both single-model and textual hierarchical MAS in quality, while simultaneously reducing tokens by more than 80% and accelerating inference by approximately four times.

However, this "telepathic" design has non-trivial engineering implications. First, LatentMAS requires compatible agent architectures: to transfer the KV cache without re-encoding, all participants in the chain must have matching layer dimensions and cache format. In the paper, the authors simply use the same Qwen3 model in different roles, which automatically fulfills this requirement. In real systems with heterogeneous models, one would either need to introduce projectors between spaces or await further research on more general schemes of latent collaboration. Second, one needs to learn to live with large and long-lived KV caches: when you don't discard CoT between agents but carry the entire history of internal states, the amount of RAM during inference becomes a new limiting constant. Here, it will be necessary to design a lifecycle policy for caches: what to log, what can be reconstructed from input, how to replay or partially truncate working memory without breaking the very idea of shared latent working memory.

The most unpleasant trade-off is, of course, interpretability. In textual MAS, any product manager can scroll through the agent chat and say: "here the planner went crazy, and here the critic missed an obvious error." In LatentMAS, between the input and the final answer, only latent multi-dimensional dynamics are hidden. The authors explicitly note that such a scheme reduces transparency and point in the future directions section to the need to combine latent and textual modes, as well as better understand and visualize the system's behavior in latent space. From an engineering perspective, the list of questions that need to be addressed before production is quite specific: how to log and replay latent traces (not just text), what metrics to build on top of hidden states and the KV cache structure, how to selectively "pass through" certain steps back into text when an explanation is needed for the user or auditor. Plus, classic security questions remain: when exchanging hidden states, agents potentially see more internal information than when exchanging truncated textual summaries, and this is a separate field for red-teaming and access policies.

However, LatentMAS is not an abstract idea from a PDF, but quite tangible code that can be explored this weekend. The authors have released the full repository and data on GitHub, with ready-made implementations for Qwen3-4B/8B/14B, as well as configurations and scripts for sequential and hierarchical MAS on major benchmarks—from GSM8K and MedQA to MBPP-Plus and HumanEval-Plus. The minimum checklist for an engineer looks like this: clone the repository, spin up one of the Qwen3 backends, run textual MAS and LatentMAS on one of the supported tasks (e.g., GSM8K or HumanEval-Plus), collect your accuracy/tokens/latency metrics, and only then decide whether to port the patterns to your stack. This is one of those rare cases where an article about how an LLM system can store and transfer latent "memories" is simultaneously an instruction for building your own "telepathic" team of agents in production code. And the main experiment here is not even about what numbers you get on benchmarks, but about what you will learn about your current agent systems if you let them "talk with thoughts" at least once instead of endless CoT memoirs.

In conclusion, LatentMAS proposes looking at a multi-agent system not as a chain of "chatting" LLMs, but as a shared computational environment where agents work with the same latent memory. Text in such an architecture becomes a thin interface only at the system boundaries, not the main carrier of meaning, which radically changes both the economics and the design of agent pipelines. The only practical question left to answer is: do you want to spend tokens on agents' conversations or invest resources in their shared field of thoughts.

Stay curious.